... newer stories

Saturday, 30. December 2006

Hussein hanged

The New York Times report that Saddam Hussein was hanged just before dawn (3 am GMT) during the morning call to prayer on Saturday, Baghdad time. The execution happened before the appeal that Hussein made was decided on and just before the Muslim celebration of Eid, which might have postponed the execution, start. His half-brother Barzan al-Tikriti and former Iraqi chief judge Awad Hamed al-Bandar are also reported to have been executed, BBC say. All three were sentenced to death by an Iraqi court on 5 November after a year-long trial over the 1982 killings of 148 Shias in the town of Dujail.

ieva jusionyte, 01:23h

... link (3 Kommentare) ... comment

farewell to objectivity: writing about genocide

Dawn was breaking in New York when an international call stirred in bed fifty-four year old Columbia University fellow. The call was from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announcing that the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Turkey’s most known contemporary writer - Orhan Pamuk. Later the same day in a telephone interview with the Associated Press O. Pamuk said that he accepted the award not just as a personal honor, but as an honor bestowed upon the Turkish literature and culture he represents. What happened on October 12, 2006, was echoed around the world in controversial headlines: “Nobel literature laureate Orhan Pamuk is voice of a divided country" (AP); “Award for Turkish writer strikes a blow for freedom” (Financial Times); “Pamuk: literary star and thorn in Turkey's side” (AFP); “Turk who defied official history wins Nobel Prize” (The Times); “Nobel prize for Turkish author who divided nation over massacres” (The Daily Telegraph); “A prize affair; Turkey and the Armenians” (The Economist).

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

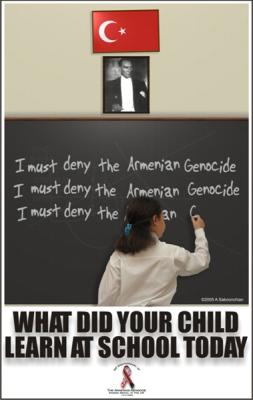

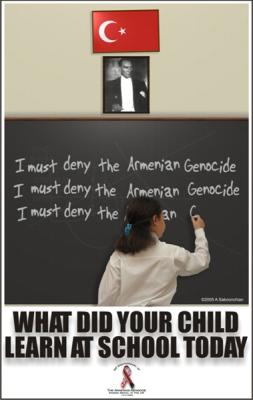

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

ieva jusionyte, 01:03h

... link (3 Kommentare) ... comment

... older stories