... newer stories

Friday, 5. January 2007

Stories from South America. Universidad

If anything, Chile is first and foremost heard of when the media reports student protests. They have been doing that during the three-year rule of left-wing Salvador Allende, then they reappeared as resistance to rightist Pinochet´s dictatorship and now, with a pro-socialist divorced mother in power (in a state that is considered rather conservative otherwise), high school students voiced their demands to Michel Bachelet.

Protests in Chile began in late April and early May with a peak on May 30, when almost eight hundred thousand students went out to the streets in demand for abolishing the fees of college entrance exams, free public transportation and identity cards. However, over the days and nights spent in nearly half of secondary schools throughout the country that were occupied, “the penguins”, who were named after the black and white uniforms that los secundarios wear at school, changed their goals to a complete reform of educational policies in Chile. These efforts have been directed against LOCE (Ley Orgánica Constitucional de Educación) – the last stab of the dictatorship at reforming Chile’s social institutions in 1990. Today in some neigborhood of Valparaiso, definitely labeled ¨NOT FOR TOURISTS¨, I saw some grafitti which said something like ¨The dictator is dead, let´s get away with his constitution¨. Augusto Pinochet died on December 10, 2006, shattering hopes of victims of the regime’s abuses that he would be brought to justice. Seventeen years that he was ruling the country where “not a leave moved if he was not moving it” strongly affected the process of democratizing education and these effects are still felt today as the largest student mobilization since the fall of dictatorship has revealed. This LOCE law is a condensation of neoliberal economic policies applied to educational system. It officially allows anyone who has the money to manage primary and secondary schools; therefore, many prestigious schools are owned by big businesses or religious organizations such as Opus Dei or the Legions pf Christ (in fact, in Chile the democratization of education has always been associated with Protestantism as opposed to hierarchical Catholicism). What is more striking is that these wealthy owners of schools are paid government subsidies per student in attendance at their school and frauds are widespread.

The process of how student demands transformed into a broad upheaval against neoliberal economics is interesting in itself. University students gave lectures to los secundarios about politics that affect the quality of education in Chile in school halls filled with the sound of reggaetón. The protests united los secundarios with their fellows in private schools as well as with university students, the Mapuches, who also struggle for educational reforms, and even workers in the health sector as well as employees of department stores. Because students have been opposing the current system which can be equated with the state, they are often situated under the label of anarchism which ascribes them to a particular niche in the popular culture. Student protesters have to a large extent merged with anarchists, communists, even the indigenous, and, therefore, developed into a broad subcultural movement of the oppressed, where oppressed is anyone who has failed to be incorporated into the unifying national discourse. But the current allegations that the students are antipatriotic and revolutionary or anarchist has a long history. As long back as in mid-1920s university students allied with the anarchists in the demonstrations to complain of nationalism’s debility and to seek a pedagogical solution to Chile’s social conundrum.

Some insights into the rhetoric of the protests in 2006 would help. For example, a call for a general national strike in a leaflet distributed by the Internationalist Workers’ Party of Chile during the “walkout” of students on June 5 sums up the interrelatedness of student demands with broader social issues:

“For free state education at every level! Down with privately owned education! Free entrance to University! The educational budget must be funded through taxing the big fortunes, refusing to pay the external debt and cutting 80% off the military budget that pays the “gurka” Chilean Armed Forces, lackeys of her the murderous Bush and Blair!

Enough of hostages packing the Pinochetista jails of the civil-military regime! Freedom now for the imprisoned fighting students, for the political prisoners of the Mapuche movement, for all the political prisoners!

As the Chilean students say, “Enough of skyrocketing copper while education is laying on the ground!” The struggle should be for the complete re-nationalization of copper under workers’ control, so that this immense wealth funds free education, workers’ health services, and bread, jobs, living wages for all working people!

The struggle for free and state owned education is the struggle of all the workers and people in Chile!”

Student organizations, such as FECH (Federación Estudiantes Universidad de Chile), have been continuously engaged in the relations of allegiance to the parties. In opposition to the leftist response presented above, that with some modifications was articulated by a number of socialist movements and media sources throughout the world, there was also a right-wing voice that, although dissatisfied with the educational system in general, did not support abolition of fees and other egalitarian aspects of the proposed reforms.

The topic of the March of the Penguins was widely discussed in Chilean and international blogs. Manuel Guerrero Antequera, whose thoughts were reprinted in the opinion section of the Cultura Libre website, writes:

“Así como la lucha contra la dictadura fue llevada adelante por una multiplicidad de fuerzas, por una variedad de cuerpos en resistencia, por un enjambre de identidades en formación, acciones y subjetividades que se disputaban, en forma directa y abierta, el espacio de la política, los estudiantes secundarios de hoy han desbordado las formas de contenido y expresión dictados por quienes creen la única voz autorizada para señalar como ha de vivirse en democracia.”

Although now 95,8 percent of Chilean population over ten years old is literate and over the last decade the number of people with higher education has grown from 9 to 16 percent, education is still connected with structures of inequality. According to some sources, which could not be verified, a survey completed last year found that only 2.1 percent of high school students from municipal schools earned the minimum score required to enter a university on the country’s college entrance exam. The problems are much more complex than articulated by the student leaders in the protests. Students from lower tier schools don’t just lack the few dozens of dollars to pay for entrance exams. They lack the preparation which is necessary to stand a chance at entering a university. Only the smartest are admitted to public universities, like the Universidad de Chile, and only those who have sufficient income dare to attend private colleges, even though officially the loan system claims to be accessible to all. Therefore, even though the concrete minor demands of student protestors have been addressed through negotiations with the Ministry of Education, the strike persisted till autumn due to complexity of students’ demands that developed as the movement expanded to include more and more groups dissatisfied with the present state of affairs.

Now it seems over. The students were included in the group that drafted proposals to the government. However, just before officially handing them to the authorities the students quit, saying they disagree and still demand the overall rewriting of the Pinochet´s constitution. The university is also empty, summer hollidays in still hot and smoggy Santiago.

Protests in Chile began in late April and early May with a peak on May 30, when almost eight hundred thousand students went out to the streets in demand for abolishing the fees of college entrance exams, free public transportation and identity cards. However, over the days and nights spent in nearly half of secondary schools throughout the country that were occupied, “the penguins”, who were named after the black and white uniforms that los secundarios wear at school, changed their goals to a complete reform of educational policies in Chile. These efforts have been directed against LOCE (Ley Orgánica Constitucional de Educación) – the last stab of the dictatorship at reforming Chile’s social institutions in 1990. Today in some neigborhood of Valparaiso, definitely labeled ¨NOT FOR TOURISTS¨, I saw some grafitti which said something like ¨The dictator is dead, let´s get away with his constitution¨. Augusto Pinochet died on December 10, 2006, shattering hopes of victims of the regime’s abuses that he would be brought to justice. Seventeen years that he was ruling the country where “not a leave moved if he was not moving it” strongly affected the process of democratizing education and these effects are still felt today as the largest student mobilization since the fall of dictatorship has revealed. This LOCE law is a condensation of neoliberal economic policies applied to educational system. It officially allows anyone who has the money to manage primary and secondary schools; therefore, many prestigious schools are owned by big businesses or religious organizations such as Opus Dei or the Legions pf Christ (in fact, in Chile the democratization of education has always been associated with Protestantism as opposed to hierarchical Catholicism). What is more striking is that these wealthy owners of schools are paid government subsidies per student in attendance at their school and frauds are widespread.

The process of how student demands transformed into a broad upheaval against neoliberal economics is interesting in itself. University students gave lectures to los secundarios about politics that affect the quality of education in Chile in school halls filled with the sound of reggaetón. The protests united los secundarios with their fellows in private schools as well as with university students, the Mapuches, who also struggle for educational reforms, and even workers in the health sector as well as employees of department stores. Because students have been opposing the current system which can be equated with the state, they are often situated under the label of anarchism which ascribes them to a particular niche in the popular culture. Student protesters have to a large extent merged with anarchists, communists, even the indigenous, and, therefore, developed into a broad subcultural movement of the oppressed, where oppressed is anyone who has failed to be incorporated into the unifying national discourse. But the current allegations that the students are antipatriotic and revolutionary or anarchist has a long history. As long back as in mid-1920s university students allied with the anarchists in the demonstrations to complain of nationalism’s debility and to seek a pedagogical solution to Chile’s social conundrum.

Some insights into the rhetoric of the protests in 2006 would help. For example, a call for a general national strike in a leaflet distributed by the Internationalist Workers’ Party of Chile during the “walkout” of students on June 5 sums up the interrelatedness of student demands with broader social issues:

“For free state education at every level! Down with privately owned education! Free entrance to University! The educational budget must be funded through taxing the big fortunes, refusing to pay the external debt and cutting 80% off the military budget that pays the “gurka” Chilean Armed Forces, lackeys of her the murderous Bush and Blair!

Enough of hostages packing the Pinochetista jails of the civil-military regime! Freedom now for the imprisoned fighting students, for the political prisoners of the Mapuche movement, for all the political prisoners!

As the Chilean students say, “Enough of skyrocketing copper while education is laying on the ground!” The struggle should be for the complete re-nationalization of copper under workers’ control, so that this immense wealth funds free education, workers’ health services, and bread, jobs, living wages for all working people!

The struggle for free and state owned education is the struggle of all the workers and people in Chile!”

Student organizations, such as FECH (Federación Estudiantes Universidad de Chile), have been continuously engaged in the relations of allegiance to the parties. In opposition to the leftist response presented above, that with some modifications was articulated by a number of socialist movements and media sources throughout the world, there was also a right-wing voice that, although dissatisfied with the educational system in general, did not support abolition of fees and other egalitarian aspects of the proposed reforms.

The topic of the March of the Penguins was widely discussed in Chilean and international blogs. Manuel Guerrero Antequera, whose thoughts were reprinted in the opinion section of the Cultura Libre website, writes:

“Así como la lucha contra la dictadura fue llevada adelante por una multiplicidad de fuerzas, por una variedad de cuerpos en resistencia, por un enjambre de identidades en formación, acciones y subjetividades que se disputaban, en forma directa y abierta, el espacio de la política, los estudiantes secundarios de hoy han desbordado las formas de contenido y expresión dictados por quienes creen la única voz autorizada para señalar como ha de vivirse en democracia.”

Although now 95,8 percent of Chilean population over ten years old is literate and over the last decade the number of people with higher education has grown from 9 to 16 percent, education is still connected with structures of inequality. According to some sources, which could not be verified, a survey completed last year found that only 2.1 percent of high school students from municipal schools earned the minimum score required to enter a university on the country’s college entrance exam. The problems are much more complex than articulated by the student leaders in the protests. Students from lower tier schools don’t just lack the few dozens of dollars to pay for entrance exams. They lack the preparation which is necessary to stand a chance at entering a university. Only the smartest are admitted to public universities, like the Universidad de Chile, and only those who have sufficient income dare to attend private colleges, even though officially the loan system claims to be accessible to all. Therefore, even though the concrete minor demands of student protestors have been addressed through negotiations with the Ministry of Education, the strike persisted till autumn due to complexity of students’ demands that developed as the movement expanded to include more and more groups dissatisfied with the present state of affairs.

Now it seems over. The students were included in the group that drafted proposals to the government. However, just before officially handing them to the authorities the students quit, saying they disagree and still demand the overall rewriting of the Pinochet´s constitution. The university is also empty, summer hollidays in still hot and smoggy Santiago.

ieva jusionyte, 23:29h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Thursday, 4. January 2007

Stories from South America. Santiago

I wanted to start the story with the image of landing in Santiago and the feelings the first breath of air in South America, the continent of my dreams from as early as I read ¨The Children of Captain Grant¨, arrose. However, this story has a life of its own and it is not in my hands to control it. And so... I was sleeping in the plane from Miami when suddently i woke up, opened the window to meet the first rays of light with my still closed eyes and saw the Andes... the undending chain of mountains, some covered with snow, their peaks fading in the horizon, others resembling a desert with no life but some bushes and villages clusttered around small streams of water, tiny rivers, flowing out of nowhere in the orange or light brown landscape. And then we landed. Santiago is hot, sunny, smoggy and very dry. Somehow I remember the interesting conversation with Randy about Chileans willing to take Bolivia and Peru´s water supplies... Even the taxi driver (i didn´t mean to take a taxi...) was complaining about that. But later on he switched to a more interesting topic of Chilean wine, nice guys I should find to marry and pisco or pisco sour, the traditional brandy-like drink with lemon juice, according to Randy, also taken from the Peruvians. But let´s leave politics aside at least for the first day I am here... I should go sight-seeing, like the normal tourists do.

Therefore, I am waiting for Diego at the very cozy hostel in Barrio Bellavista, a neighborhood built by artists, somewhat similar to Uzupis in Lithuania... listening to some relaxing jazz tunes in the presence of Che Guevara and Merilyn Monroe´s photos on the red walls... and thinking which of the books to take... travellers leave a lot of them here... Umberto Eco, Truman Capote, Milan Kundera, Paolo Coelho... there is also a small black dog, sleeping in the shade and running around welcoming every guest. And, sure, there is a Christmas tree, just by the doorway to a blossoming garden. It´s summer in the other end of the world, but still with Santas...

So this is what Diego´s (who is native of Santiago, but normally has little time to explore it) and my day was like in the city of 5 or 6 million inhabitants founded by the Spanish in 1541...

Because of the smog, which stays here forever as the Andes block the winds, the snowy tops of the mountains are not seen in the distance. The ugly modern buildings are from the 1970s. The view from Cerro Santa Lucia, the beginning of Valdivia´s town...

Museo de Bellas Artes...

On the way to Universidad de Chile...

Catedral Metropolitana in the Plaza de Armas, also the first to be populated by the colonists...

Palacio de la Moneda, where president Michele Bachelet resides. Still guarded, but visitors are welcome after Pinochet´s era...

Even the dogs were lazy in 36 degrees Celsius.

Therefore, I am waiting for Diego at the very cozy hostel in Barrio Bellavista, a neighborhood built by artists, somewhat similar to Uzupis in Lithuania... listening to some relaxing jazz tunes in the presence of Che Guevara and Merilyn Monroe´s photos on the red walls... and thinking which of the books to take... travellers leave a lot of them here... Umberto Eco, Truman Capote, Milan Kundera, Paolo Coelho... there is also a small black dog, sleeping in the shade and running around welcoming every guest. And, sure, there is a Christmas tree, just by the doorway to a blossoming garden. It´s summer in the other end of the world, but still with Santas...

So this is what Diego´s (who is native of Santiago, but normally has little time to explore it) and my day was like in the city of 5 or 6 million inhabitants founded by the Spanish in 1541...

Because of the smog, which stays here forever as the Andes block the winds, the snowy tops of the mountains are not seen in the distance. The ugly modern buildings are from the 1970s. The view from Cerro Santa Lucia, the beginning of Valdivia´s town...

Museo de Bellas Artes...

On the way to Universidad de Chile...

Catedral Metropolitana in the Plaza de Armas, also the first to be populated by the colonists...

Palacio de la Moneda, where president Michele Bachelet resides. Still guarded, but visitors are welcome after Pinochet´s era...

Even the dogs were lazy in 36 degrees Celsius.

ieva jusionyte, 10:55h

... link (2 Kommentare) ... comment

Monday, 1. January 2007

crime in Boston

On New Year's Night, just two blocks away from the South Station in Boston, city full of people loudly celebrating the coming of 2007, a black man was shot multiple times from a car. He was the 74th victim of homicide in Boston in 2006.

"The Boston Globe" in the edition of January 1, 2007, reports the statistics of crime in the capital of New England last year.

Of the 73 people that were killed:

61 were black, 8 Hispanic (any race), 11 white and 1 Asian;

66 were male and 7 were female;

38 were between 14 and 25 years old, 29 had between 26 and 44 years, 5 were older than 49 and 1 was younger than than 5 years old;

most of them were killed in the months of May, June, July and October on weekends and Mondays between 8 PM and 3 AM in the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury and Mattapan;

54 died of gunshot wounds, 13 were stabbed with a knife and 6 died due to other trauma;

ONLY 36 percent of the murder cases were solved.

"The Boston Globe" in the edition of January 1, 2007, reports the statistics of crime in the capital of New England last year.

Of the 73 people that were killed:

61 were black, 8 Hispanic (any race), 11 white and 1 Asian;

66 were male and 7 were female;

38 were between 14 and 25 years old, 29 had between 26 and 44 years, 5 were older than 49 and 1 was younger than than 5 years old;

most of them were killed in the months of May, June, July and October on weekends and Mondays between 8 PM and 3 AM in the neighborhoods of Dorchester, Roxbury and Mattapan;

54 died of gunshot wounds, 13 were stabbed with a knife and 6 died due to other trauma;

ONLY 36 percent of the murder cases were solved.

ieva jusionyte, 18:05h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Sunday, 31. December 2006

2006-2007

The last news of 2006 and the first news of 2007:

"The New York Times" remembers the faces of 3000 individuals who have died in Iraq, the first death - that of Jay Aubin from marine corps - dating back to March 21, 2003, and the last one - that of the twenty-year old William Spencer - December 28, 2006. A must-see interactive square: http://www.nytimes.com/ref/us/20061228_3000FACES_TAB1.html.

It was still December 31 when Belarus and Russia reached a deal on gas - a sign that Belarussians will not have to suffer from cold like the Ukrainians did last year. Minsk will have to pay 100 dollars per 1000 cubic metres of gas, which is 5 dollars below the price demanded by Russia that was threatening to halt supplies on Monday, January 1. Until now Belarus used to pay 47 dollars for the same amount of gas to "Gazprom", according to which the change reflects market prices and has no political agenda.

From now on the European Union has twenty-seven members and half a million citizens as two more states from Eastern Europe - Romania and Bulgaria - joined the club at midnight on New Year's Day. More: http://euobserver.com/9/23154.

The on-line news portal where I used to work changed from Omni.lt to http://www.balsas.lt/. Balsas (Lithuanian) = the voice.

"The New York Times" remembers the faces of 3000 individuals who have died in Iraq, the first death - that of Jay Aubin from marine corps - dating back to March 21, 2003, and the last one - that of the twenty-year old William Spencer - December 28, 2006. A must-see interactive square: http://www.nytimes.com/ref/us/20061228_3000FACES_TAB1.html.

It was still December 31 when Belarus and Russia reached a deal on gas - a sign that Belarussians will not have to suffer from cold like the Ukrainians did last year. Minsk will have to pay 100 dollars per 1000 cubic metres of gas, which is 5 dollars below the price demanded by Russia that was threatening to halt supplies on Monday, January 1. Until now Belarus used to pay 47 dollars for the same amount of gas to "Gazprom", according to which the change reflects market prices and has no political agenda.

From now on the European Union has twenty-seven members and half a million citizens as two more states from Eastern Europe - Romania and Bulgaria - joined the club at midnight on New Year's Day. More: http://euobserver.com/9/23154.

The on-line news portal where I used to work changed from Omni.lt to http://www.balsas.lt/. Balsas (Lithuanian) = the voice.

ieva jusionyte, 20:29h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

blood diamonds

Fact #1: An estimated 5 million people have access to appropriate healthcare globally thanks to revenues from diamonds.

Fact #3: An estimated 10 million people globally are directly or indirectly supported by the diamond industry.

Fact #4: The diamond mining industry generates over 40% of Namibia's annual export earnings.

Fact #8: Approximately one million people are employed by the diamond industry in India.

Fact #9: Approximately $8.4 billion worth of diamonds (64 percent of the world‘s diamonds) a year come from African countries.

Fact #12: The revenue from diamonds is instrumental in the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

This information comes from the World Diamond Council (WDC) website – http://www.diamondfacts.org/, an umbrella structure representing over fifty industry organizations from all over the world – the U.S., Russia, Israel, South Africa and Belgium with the historic diamond trading center in Antwerp, to name just a few. Having in mind that diamond supply and distribution is concentrated in the hands of a few key players, it is obvious that this network will make use of all means in order to make money from the diamond business. They have page-size advertisements in “The New York Times” where the above mentioned facts are used to prove how much benefit to the world and to its poor comes from diamond trade.

What might be interesting is that one of these organizations united under the WDC is “De Beers”, a Johannesburg-based corporation, which in the 1980s had a near monopoly (80 percent) on the world’s diamond trade and later was charged with antitrust violations for conspiring to fix prices for industrial diamonds.

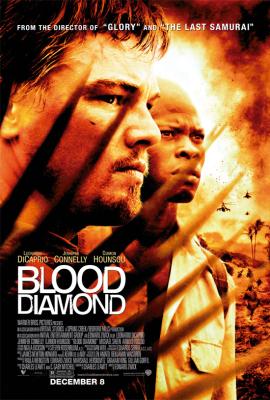

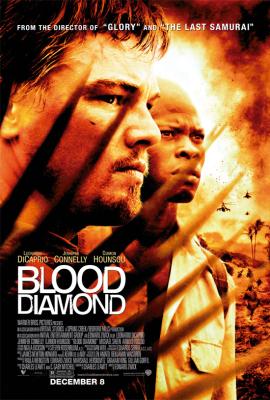

But diamond industry might need more than such PR campaigns to recover their revenues after the release of Warner Bros movie “The Blood Diamond” (http://blooddiamondmovie.warnerbros.com/).

The term “blood diamonds” refers to conflict diamonds, which the UN defines as "...diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council." Although this issue attracted the attention of the world when during the civil war in Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002 the rebels took over diamond mines, conflict diamonds have also been used to fund conflicts in Liberia, whose president Charles Taylor was accused by the UN of backing the insurgency in Sierra Leone, also Cote d'Ivoire, Angola, Congo and former Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. As Amnesty International reports, blood diamonds that have fueled wars across Africa led to the deaths of more than 4 million people and displacing many millions more. The extent of the problem becomes clear if one more fact is introduced – the most commercially viable diamond deposits in the world are nowhere else but in Africa and the same conflict-ridden countries are listed as the ones that have most of them.

According to the WDC, conflict diamonds have been reduced from approximately 4% to less than 1% since the implementation of the Kimberley Process on which, under the pressure from the UN to stop the flow of conflict diamonds, governments, NGOs and diamond industry agreed in 2003. Under this system, rough diamonds are sealed in tamper-resistant containers and accompanied by forgery resistant certificates with serial numbers each time they cross an international border. However, Liberia and Congo are not part of this process. And there are many more gaps in this system. For example, the borders in Africa are very porous and trafficking across them is persistent. When the blood diamonds enter states that are not technically defined as being at war, they become “clean”. According to Amnesty International and Global Witness, diamonds from rebel-held areas in the north of Cote d'Ivoire, Liberia or eastern DRC are smuggled into neighboring countries and exported as part of the legitimate diamond trade.

The WDC website, created to erase any suspicion of the consumers, confused about whether to buy wedding rings with the precious stones for the production of which people might have died, continues to write that today in Sierra Leone “diamonds represent a resource of crucial importance to the development of the country as it exported approximately $142 million worth of diamonds (approximately 3% of the world's diamonds) in 2005. Revenues from diamond exports are making a positive contribution to the rebuilding of its infrastructure, health services and education systems.” The language of blood, conflict, civil war is converted into the vocabulary of development. Following this logic, as Marilyn Monroe was singing in the 1953 film “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend”… and buying them will even help the victims of famine and AIDS.

Not everyone knows more. It is a stunning fact but in 2006 Grammy Award for the Best Rap Song was awarded to Kanye West for the song “Diamonds from Sierra Leone” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6B8nlkUlb/), but only after making this song did the U.S. rapper find out about the issue of conflict diamonds and children mining them in West Africa. Global Witness, Amnesty International and the creators of the movie “Blood Diamond” are supporting a website “Blood Diamond Action” - http://www.blooddiamondaction.org/ - and some consumer guides have been written for those who still want to buy diamonds but, for the sake of good conscience, make sure that they are conflict-free.

The issue of diamond trade and its role in both violent conflicts and developmental processes is very complex, but needs to be addressed and even a Hollywood movie is instrumental in raising public awareness.

Fact #3: An estimated 10 million people globally are directly or indirectly supported by the diamond industry.

Fact #4: The diamond mining industry generates over 40% of Namibia's annual export earnings.

Fact #8: Approximately one million people are employed by the diamond industry in India.

Fact #9: Approximately $8.4 billion worth of diamonds (64 percent of the world‘s diamonds) a year come from African countries.

Fact #12: The revenue from diamonds is instrumental in the fight against the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

This information comes from the World Diamond Council (WDC) website – http://www.diamondfacts.org/, an umbrella structure representing over fifty industry organizations from all over the world – the U.S., Russia, Israel, South Africa and Belgium with the historic diamond trading center in Antwerp, to name just a few. Having in mind that diamond supply and distribution is concentrated in the hands of a few key players, it is obvious that this network will make use of all means in order to make money from the diamond business. They have page-size advertisements in “The New York Times” where the above mentioned facts are used to prove how much benefit to the world and to its poor comes from diamond trade.

What might be interesting is that one of these organizations united under the WDC is “De Beers”, a Johannesburg-based corporation, which in the 1980s had a near monopoly (80 percent) on the world’s diamond trade and later was charged with antitrust violations for conspiring to fix prices for industrial diamonds.

But diamond industry might need more than such PR campaigns to recover their revenues after the release of Warner Bros movie “The Blood Diamond” (http://blooddiamondmovie.warnerbros.com/).

The term “blood diamonds” refers to conflict diamonds, which the UN defines as "...diamonds that originate from areas controlled by forces or factions opposed to legitimate and internationally recognized governments, and are used to fund military action in opposition to those governments, or in contravention of the decisions of the Security Council." Although this issue attracted the attention of the world when during the civil war in Sierra Leone between 1991 and 2002 the rebels took over diamond mines, conflict diamonds have also been used to fund conflicts in Liberia, whose president Charles Taylor was accused by the UN of backing the insurgency in Sierra Leone, also Cote d'Ivoire, Angola, Congo and former Zaire, now known as the Democratic Republic of Congo. As Amnesty International reports, blood diamonds that have fueled wars across Africa led to the deaths of more than 4 million people and displacing many millions more. The extent of the problem becomes clear if one more fact is introduced – the most commercially viable diamond deposits in the world are nowhere else but in Africa and the same conflict-ridden countries are listed as the ones that have most of them.

According to the WDC, conflict diamonds have been reduced from approximately 4% to less than 1% since the implementation of the Kimberley Process on which, under the pressure from the UN to stop the flow of conflict diamonds, governments, NGOs and diamond industry agreed in 2003. Under this system, rough diamonds are sealed in tamper-resistant containers and accompanied by forgery resistant certificates with serial numbers each time they cross an international border. However, Liberia and Congo are not part of this process. And there are many more gaps in this system. For example, the borders in Africa are very porous and trafficking across them is persistent. When the blood diamonds enter states that are not technically defined as being at war, they become “clean”. According to Amnesty International and Global Witness, diamonds from rebel-held areas in the north of Cote d'Ivoire, Liberia or eastern DRC are smuggled into neighboring countries and exported as part of the legitimate diamond trade.

The WDC website, created to erase any suspicion of the consumers, confused about whether to buy wedding rings with the precious stones for the production of which people might have died, continues to write that today in Sierra Leone “diamonds represent a resource of crucial importance to the development of the country as it exported approximately $142 million worth of diamonds (approximately 3% of the world's diamonds) in 2005. Revenues from diamond exports are making a positive contribution to the rebuilding of its infrastructure, health services and education systems.” The language of blood, conflict, civil war is converted into the vocabulary of development. Following this logic, as Marilyn Monroe was singing in the 1953 film “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes”, “diamonds are a girl’s best friend”… and buying them will even help the victims of famine and AIDS.

Not everyone knows more. It is a stunning fact but in 2006 Grammy Award for the Best Rap Song was awarded to Kanye West for the song “Diamonds from Sierra Leone” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U6B8nlkUlb/), but only after making this song did the U.S. rapper find out about the issue of conflict diamonds and children mining them in West Africa. Global Witness, Amnesty International and the creators of the movie “Blood Diamond” are supporting a website “Blood Diamond Action” - http://www.blooddiamondaction.org/ - and some consumer guides have been written for those who still want to buy diamonds but, for the sake of good conscience, make sure that they are conflict-free.

The issue of diamond trade and its role in both violent conflicts and developmental processes is very complex, but needs to be addressed and even a Hollywood movie is instrumental in raising public awareness.

ieva jusionyte, 01:01h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Saturday, 30. December 2006

Hussein hanged

The New York Times report that Saddam Hussein was hanged just before dawn (3 am GMT) during the morning call to prayer on Saturday, Baghdad time. The execution happened before the appeal that Hussein made was decided on and just before the Muslim celebration of Eid, which might have postponed the execution, start. His half-brother Barzan al-Tikriti and former Iraqi chief judge Awad Hamed al-Bandar are also reported to have been executed, BBC say. All three were sentenced to death by an Iraqi court on 5 November after a year-long trial over the 1982 killings of 148 Shias in the town of Dujail.

ieva jusionyte, 01:23h

... link (3 Kommentare) ... comment

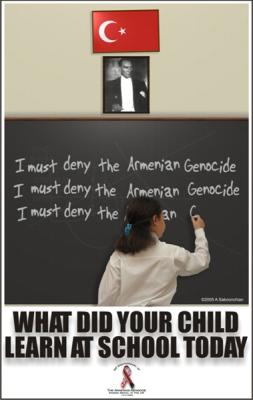

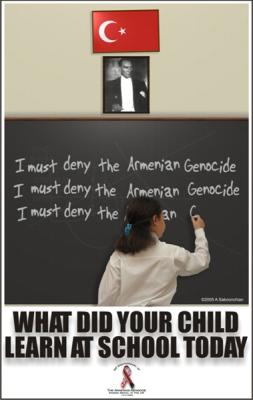

farewell to objectivity: writing about genocide

Dawn was breaking in New York when an international call stirred in bed fifty-four year old Columbia University fellow. The call was from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announcing that the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Turkey’s most known contemporary writer - Orhan Pamuk. Later the same day in a telephone interview with the Associated Press O. Pamuk said that he accepted the award not just as a personal honor, but as an honor bestowed upon the Turkish literature and culture he represents. What happened on October 12, 2006, was echoed around the world in controversial headlines: “Nobel literature laureate Orhan Pamuk is voice of a divided country" (AP); “Award for Turkish writer strikes a blow for freedom” (Financial Times); “Pamuk: literary star and thorn in Turkey's side” (AFP); “Turk who defied official history wins Nobel Prize” (The Times); “Nobel prize for Turkish author who divided nation over massacres” (The Daily Telegraph); “A prize affair; Turkey and the Armenians” (The Economist).

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

ieva jusionyte, 01:03h

... link (3 Kommentare) ... comment

... older stories