Tuesday, 23. January 2007

Hrant's funeral

Today in Istanbul hundreds of thousands are saying good-bye to Hrant Dink, murnered in front of his newspaper's offices last Friday.

(picture from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/english/5823943.asp#)

Here is the last editorial of the Turkish-Armenian writer and journalist:

"The Pigeon-like Unease of My Inner Spirit"

by Hrant Dink

AGOS Newspaper

10 January 2007

I did not at first feel troubled about the investigation that was filed against me by the Şişli public prosecutor’s office with the accusation of “insulting Turkishness.” This was not the first time. I had been familiar to the accusation because of a similar lawsuit I had filed against me in Urfa. I was being tried in Urfa with the accusation of “denigrating Turkishness” over the past three years for having stated in a talk I gave at a conference there in 2002 that “I was not a Turk…but from Turkey and an Armenian.” And I was even unaware about how the lawsuit was proceeding. I was not at all interested. My lawyer friends in Urfa were attending the hearings in my absence.

I was even quite nonchalant when I went and gave my deposition to the Şişli public prosecutor. I ultimately had complete trust in what my intentions had been and what I had written. Once the prosecutor [had the chance] to evaluated not that single sentence from my editorial alone which made no sense by itself but the text as a whole, he would understand with great ease that I had no intention to “denigrate Turkishness” and this comedy would come to an end.

I was certain that a lawsuit would not be filed at the end of the investigation. I was sure of myself. But surprise! A lawsuit was filed.

But I still did not lose my optimism.

So much so that at a television show that I joined live, I even told the lawyer [Kemal] Kerincsiz who was accusing me “that he should not get his hopes too high, that I was not going to be smacked with any sentence from this lawsuit, and that I would leave this country if I received a sentence.” I was sure of myself because I truly had not had in my article any premeditation or intention – not even a single iota – to denigrate Turkishness. Those who read the entirety of my collection of articles would understand this very clearly.

As a matter of fact, the report prepared by the three faculty members from Istanbul University who had been appointed by the court as experts stated exactly that. There was no reason for me to get troubled, there would certainly be a return from the wrongful path [of the lawsuit] at one stage of the proceedings or the other. So I kept asking for patience… But there was no such return.

The prosecutor asked for a sentence in spite of the expert report. The judge then sentenced me to six months in prison. When I first heard about my sentence, I found myself under the bitter pressure of the hopes I had nurtured all along the process of the lawsuit. I was bewildered… My disappointment and rebellion were at their pinnacle.

I had resisted for days and months saying “just you wait for this decision to come out and once I am acquitted, then you will all be so repentant about all that you have said and written.”

In covering every hearing of the lawsuit, the newspapers items, editorials and television programs all referred to how I had said that “the blood of the Turk is poisonous.” Each and every time, they were adding to my fame as “the enemy of the Turk.” At the halls of the court, the fascists physically attacked me with racist curses. They bombarded me with insults on their placards. The threats reaching hundreds that kept hailing for months through phones, e-mail and letters kept increasing each time.

And I persevered through all this with patience awaiting the decision for acquittal. Once the legal decision was announced, the truth was going to prevail and all these people would be ashamed of what they had done.

My only weapon was my sincerity. But here the decision was out and all my hopes were crushed. From then on, I was in the most distressed situation that a person could possibly be in. The judge had made a decision in the name of the “Turkish nation” and had it legally registered that I had “denigrated Turkishness.” I could have persevered through anything except this. According to my understanding, racism was the denigration by anyone of a person they lived alongside with on the basis of any difference, ethnic or religious and there was not any way in which this could ever be forgiven. Well it was in this psychological state that I made the following declaration to the members of the media and friends who were at my doorstep trying to confirm “as to whether I would leave this country as I had indicated earlier:” “I shall consult with my lawyers. I will appeal at the supreme court of appeal and will even go to the European Court of Human Rights if necessary. If I am not cleared through any one of these processes, then I shall leave my country. Because according to my opinion, someone who has been sentenced with such a crime does not have the right to live alongside the citizens whom he has denigrated.”

As I voiced this opinion, I was emotional as always. My only weapon was my sincerity.

Dark Humor

But it so happens that the deep force that was trying to single me out and make me an open target in the eyes of the people of Turkey found something wrong with this press release of mine as well and this time filed a lawsuit against me for attempting to influence the court. The entire Turkish media had given my declaration but what got their attention was what was writ in AGOS alone. And it so transpired that the legally responsible parties in the AGOS newspaper and I started to be tried this time around for attempting to influence the court. This must be what people call “dark humor.”

As I am the accused, who has the right more than the accused to try to influence the judiciary? But look at this humorous situation that the accused is this time tried for trying to influence the judiciary.

“In the Name of the Turkish State”

I have to confess that I had more than lost my trust in the concept of “Law” and the “System of Justice” in Turkey. How could I have not? Had these prosecutors, these judges not been educated in the university, graduated from faculties of law? Weren’t they supposed to have the capacity to comprehend [and interpret] what they read? But it so transpires that the judiciary in this country, as also expressed without compunction by many a statesman and politician, is not independent. The judiciary does not protect the rights of the citizen, but instead the State. The judiciary is not there for the citizen, but under the control of the State.

As a matter of fact I was absolutely sure that even though it was stated that the decision in my case was reached “in the name of the Turkish nation,” it was a decision clearly not made “on behalf of the Turkish nation” but rather “on behalf of the Turkish state.” As a consequence, my lawyers were going to appeal the Supreme Court of Appeals, but what could guarantee that the deep forces that had decided to put me in my place would not be influential there either?

And was it the case that the Supreme Court of Appeals always reached right decisions?

Wasn’t it the same Supreme Court of Appeal that had signed onto the unjust decision that stripped minority foundations of their properties? [And had done so] in spite of the attempts of the Chief Public Prosecutor.

And we did appeal and what did it get us?

Just like the report of the experts, the Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals stated that there was no evidence of crime and asked for my acquittal but the Supreme Court of Appeals still found me guilty.

The Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals was just as certain about what he had read and understood as I had been about what I had written, so he objected to the decision and took the lawsuit to the General Council. But what can I say, that great force which had decided once and for all to put me in my place and had made itself felt at every stage of my lawsuit through processes I would not even know about was there present once again behind the scenes. And as a consequence, it was declared by majority vote at General Council as well that I had denigrated Turkishness.

Like a Pigeon

This much is crystal clear that those who tried to single me out, render me weak and defenseless succeeded by their own measures. With the wrongful and polluted knowledge they oozed into society, they managed to form a significant segment of the population whose numbers cannot be easily dismissed who view Hrant Dink as someone “denigrating Turkishness.”

The diary and memory of my computer are filled with angry, threatening lines sent by citizens from this particular sector. (Let me note here at this juncture that even though one of these letters was sent from [the neighboring city of] Bursa and that I had found it rather disturbing because of the proximity of the danger it represented and [therefore] turned the threatening letter over to the Şişli prosecutor’s office, I have not been able to get a result until this day.)

How real or unreal are these threats? To be honest, it is of course impossible for me to know for sure.

What it truly threatening and unbearable for me is the psychological torture I personally place myself in. “Now what are these people thinking about me?” is the question that really bugs me.

It is unfortunate that I am now better known than I once was and I feel much more the people throwing me that glance of “Oh, look, isn’t he that Armenian guy?” And I reflexively start torturing myself.

One aspect of this torture is curiosity, the other unease. One aspect is attention, the other apprehension. I am just like a pigeon….. Obsessed just as much what goes on my left, right, front, back. My head is just as mobile… and fast enough to turn right away.

And Here is the Cost for You

What did the Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül state? The Justice Minister Cemil Çiçek?

“Come on, there is nothing to exaggerate about [legal code 301]. Is there anyone who has actually been tried and imprisoned from it?”

As if the only cost one paid was imprisonment...

Here is a cost for you... Here is a cost...

Do you know, oh ministers, what kind of a cost it is to imprison a human being into the apprehensiveness of a pigeon?... Do you know?....

You, don’t you ever watch a pigeon?

What They Call “Life-or-Death”

What I have lived through has not been an easy process… And what we have lived through as a family…

There were moments when I seriously thought about leaving the country and moving far away.

And especially when the threats started to involve those close to me…

At that point I always remained helpless.

That must be what they call “Life-or-Death.” I could have resisted out of my own will, but I did not have the right to put into danger the life of anyone who was close to me. I could have been my own hero, but I did not have the right to be brave by placing, let along someone close to me, any other person in danger.

During such helpless times, I gathered my family, my children together and sought refuge in them and received the greatest support from them. They trusted in me. Wherever I would be, they would be there as well.

If I said “let’s go” they would go, if I said “let’s stay” they would come.

To Stay and Resist

Okay, but if we went, where would we go?

To the Armenian Republic?

How long someone like me who could not stand injustices put up with the injustices there? Would not I get into even deeper trouble there? To go and live in the European countries was not at all the thing for me.

After all, I am such a person that if I travel to the West for three days, I miss my country on the fourth and start writhing in boredom saying “let this be over so I can go back,” so what would I end up doing there?

The comfort there would have gotten to me!

Leaving “boiling hells” for “ready-made heavens” was not at all right for my personality make up.

We were people who volunteered to transform the hells they lived into heavens.

To stay and live in Turkey was necessary because we truly desired it and [had to do so] out of respect to the thousands of friends in Turkey who gave a struggle for democracy and who supported us.

We were going to stay and we were going to resist.

If we were forced to leave one day however... We were going to set out just as in 1915...Like our ancestors... Without knowing where we were going... Walking the roads they walked through... Feeling the ordeal, experiencing the pain....

With such a reproach we were going to leave our homeland. And we would go where our feet took us, but not our hearts.

Apprehensive and Free

I wish that we would never ever have to experience such a departure. We have way too many reasons and hope not to experience it anyhow. Now I am applying to the European Court of Human Rights.

How long this lawsuit will last, I do not know.

The fact that I do know and that somewhat puts me at ease is that I will be living in Turkey at least until the lawsuit is finalized.

If the court decides in my favor, I will undoubtedly become very happy and it would mean that I would never have to leave my country.

From my own vantage point, 2007 will probably be even a more difficult year.

The trials will continue, new ones will commence. Who knows what kinds of additional injustices I would have to confront?

While all these occur, I will consider this one truth my only security.

Yes, I may perceive myself in the spiritual unease of a pigeon, but I do know that in this country people do not touch pigeons.

Pigeons live their lives all the way deep into the city, even amidst the human throngs.

Yes, somewhat apprehensive but just as much free.

(translated by F.M. Gocek)

(picture from http://www.hurriyet.com.tr/english/5823943.asp#)

Here is the last editorial of the Turkish-Armenian writer and journalist:

"The Pigeon-like Unease of My Inner Spirit"

by Hrant Dink

AGOS Newspaper

10 January 2007

I did not at first feel troubled about the investigation that was filed against me by the Şişli public prosecutor’s office with the accusation of “insulting Turkishness.” This was not the first time. I had been familiar to the accusation because of a similar lawsuit I had filed against me in Urfa. I was being tried in Urfa with the accusation of “denigrating Turkishness” over the past three years for having stated in a talk I gave at a conference there in 2002 that “I was not a Turk…but from Turkey and an Armenian.” And I was even unaware about how the lawsuit was proceeding. I was not at all interested. My lawyer friends in Urfa were attending the hearings in my absence.

I was even quite nonchalant when I went and gave my deposition to the Şişli public prosecutor. I ultimately had complete trust in what my intentions had been and what I had written. Once the prosecutor [had the chance] to evaluated not that single sentence from my editorial alone which made no sense by itself but the text as a whole, he would understand with great ease that I had no intention to “denigrate Turkishness” and this comedy would come to an end.

I was certain that a lawsuit would not be filed at the end of the investigation. I was sure of myself. But surprise! A lawsuit was filed.

But I still did not lose my optimism.

So much so that at a television show that I joined live, I even told the lawyer [Kemal] Kerincsiz who was accusing me “that he should not get his hopes too high, that I was not going to be smacked with any sentence from this lawsuit, and that I would leave this country if I received a sentence.” I was sure of myself because I truly had not had in my article any premeditation or intention – not even a single iota – to denigrate Turkishness. Those who read the entirety of my collection of articles would understand this very clearly.

As a matter of fact, the report prepared by the three faculty members from Istanbul University who had been appointed by the court as experts stated exactly that. There was no reason for me to get troubled, there would certainly be a return from the wrongful path [of the lawsuit] at one stage of the proceedings or the other. So I kept asking for patience… But there was no such return.

The prosecutor asked for a sentence in spite of the expert report. The judge then sentenced me to six months in prison. When I first heard about my sentence, I found myself under the bitter pressure of the hopes I had nurtured all along the process of the lawsuit. I was bewildered… My disappointment and rebellion were at their pinnacle.

I had resisted for days and months saying “just you wait for this decision to come out and once I am acquitted, then you will all be so repentant about all that you have said and written.”

In covering every hearing of the lawsuit, the newspapers items, editorials and television programs all referred to how I had said that “the blood of the Turk is poisonous.” Each and every time, they were adding to my fame as “the enemy of the Turk.” At the halls of the court, the fascists physically attacked me with racist curses. They bombarded me with insults on their placards. The threats reaching hundreds that kept hailing for months through phones, e-mail and letters kept increasing each time.

And I persevered through all this with patience awaiting the decision for acquittal. Once the legal decision was announced, the truth was going to prevail and all these people would be ashamed of what they had done.

My only weapon was my sincerity. But here the decision was out and all my hopes were crushed. From then on, I was in the most distressed situation that a person could possibly be in. The judge had made a decision in the name of the “Turkish nation” and had it legally registered that I had “denigrated Turkishness.” I could have persevered through anything except this. According to my understanding, racism was the denigration by anyone of a person they lived alongside with on the basis of any difference, ethnic or religious and there was not any way in which this could ever be forgiven. Well it was in this psychological state that I made the following declaration to the members of the media and friends who were at my doorstep trying to confirm “as to whether I would leave this country as I had indicated earlier:” “I shall consult with my lawyers. I will appeal at the supreme court of appeal and will even go to the European Court of Human Rights if necessary. If I am not cleared through any one of these processes, then I shall leave my country. Because according to my opinion, someone who has been sentenced with such a crime does not have the right to live alongside the citizens whom he has denigrated.”

As I voiced this opinion, I was emotional as always. My only weapon was my sincerity.

Dark Humor

But it so happens that the deep force that was trying to single me out and make me an open target in the eyes of the people of Turkey found something wrong with this press release of mine as well and this time filed a lawsuit against me for attempting to influence the court. The entire Turkish media had given my declaration but what got their attention was what was writ in AGOS alone. And it so transpired that the legally responsible parties in the AGOS newspaper and I started to be tried this time around for attempting to influence the court. This must be what people call “dark humor.”

As I am the accused, who has the right more than the accused to try to influence the judiciary? But look at this humorous situation that the accused is this time tried for trying to influence the judiciary.

“In the Name of the Turkish State”

I have to confess that I had more than lost my trust in the concept of “Law” and the “System of Justice” in Turkey. How could I have not? Had these prosecutors, these judges not been educated in the university, graduated from faculties of law? Weren’t they supposed to have the capacity to comprehend [and interpret] what they read? But it so transpires that the judiciary in this country, as also expressed without compunction by many a statesman and politician, is not independent. The judiciary does not protect the rights of the citizen, but instead the State. The judiciary is not there for the citizen, but under the control of the State.

As a matter of fact I was absolutely sure that even though it was stated that the decision in my case was reached “in the name of the Turkish nation,” it was a decision clearly not made “on behalf of the Turkish nation” but rather “on behalf of the Turkish state.” As a consequence, my lawyers were going to appeal the Supreme Court of Appeals, but what could guarantee that the deep forces that had decided to put me in my place would not be influential there either?

And was it the case that the Supreme Court of Appeals always reached right decisions?

Wasn’t it the same Supreme Court of Appeal that had signed onto the unjust decision that stripped minority foundations of their properties? [And had done so] in spite of the attempts of the Chief Public Prosecutor.

And we did appeal and what did it get us?

Just like the report of the experts, the Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals stated that there was no evidence of crime and asked for my acquittal but the Supreme Court of Appeals still found me guilty.

The Chief Public Prosecutor of the Supreme Court of Appeals was just as certain about what he had read and understood as I had been about what I had written, so he objected to the decision and took the lawsuit to the General Council. But what can I say, that great force which had decided once and for all to put me in my place and had made itself felt at every stage of my lawsuit through processes I would not even know about was there present once again behind the scenes. And as a consequence, it was declared by majority vote at General Council as well that I had denigrated Turkishness.

Like a Pigeon

This much is crystal clear that those who tried to single me out, render me weak and defenseless succeeded by their own measures. With the wrongful and polluted knowledge they oozed into society, they managed to form a significant segment of the population whose numbers cannot be easily dismissed who view Hrant Dink as someone “denigrating Turkishness.”

The diary and memory of my computer are filled with angry, threatening lines sent by citizens from this particular sector. (Let me note here at this juncture that even though one of these letters was sent from [the neighboring city of] Bursa and that I had found it rather disturbing because of the proximity of the danger it represented and [therefore] turned the threatening letter over to the Şişli prosecutor’s office, I have not been able to get a result until this day.)

How real or unreal are these threats? To be honest, it is of course impossible for me to know for sure.

What it truly threatening and unbearable for me is the psychological torture I personally place myself in. “Now what are these people thinking about me?” is the question that really bugs me.

It is unfortunate that I am now better known than I once was and I feel much more the people throwing me that glance of “Oh, look, isn’t he that Armenian guy?” And I reflexively start torturing myself.

One aspect of this torture is curiosity, the other unease. One aspect is attention, the other apprehension. I am just like a pigeon….. Obsessed just as much what goes on my left, right, front, back. My head is just as mobile… and fast enough to turn right away.

And Here is the Cost for You

What did the Foreign Minister Abdullah Gül state? The Justice Minister Cemil Çiçek?

“Come on, there is nothing to exaggerate about [legal code 301]. Is there anyone who has actually been tried and imprisoned from it?”

As if the only cost one paid was imprisonment...

Here is a cost for you... Here is a cost...

Do you know, oh ministers, what kind of a cost it is to imprison a human being into the apprehensiveness of a pigeon?... Do you know?....

You, don’t you ever watch a pigeon?

What They Call “Life-or-Death”

What I have lived through has not been an easy process… And what we have lived through as a family…

There were moments when I seriously thought about leaving the country and moving far away.

And especially when the threats started to involve those close to me…

At that point I always remained helpless.

That must be what they call “Life-or-Death.” I could have resisted out of my own will, but I did not have the right to put into danger the life of anyone who was close to me. I could have been my own hero, but I did not have the right to be brave by placing, let along someone close to me, any other person in danger.

During such helpless times, I gathered my family, my children together and sought refuge in them and received the greatest support from them. They trusted in me. Wherever I would be, they would be there as well.

If I said “let’s go” they would go, if I said “let’s stay” they would come.

To Stay and Resist

Okay, but if we went, where would we go?

To the Armenian Republic?

How long someone like me who could not stand injustices put up with the injustices there? Would not I get into even deeper trouble there? To go and live in the European countries was not at all the thing for me.

After all, I am such a person that if I travel to the West for three days, I miss my country on the fourth and start writhing in boredom saying “let this be over so I can go back,” so what would I end up doing there?

The comfort there would have gotten to me!

Leaving “boiling hells” for “ready-made heavens” was not at all right for my personality make up.

We were people who volunteered to transform the hells they lived into heavens.

To stay and live in Turkey was necessary because we truly desired it and [had to do so] out of respect to the thousands of friends in Turkey who gave a struggle for democracy and who supported us.

We were going to stay and we were going to resist.

If we were forced to leave one day however... We were going to set out just as in 1915...Like our ancestors... Without knowing where we were going... Walking the roads they walked through... Feeling the ordeal, experiencing the pain....

With such a reproach we were going to leave our homeland. And we would go where our feet took us, but not our hearts.

Apprehensive and Free

I wish that we would never ever have to experience such a departure. We have way too many reasons and hope not to experience it anyhow. Now I am applying to the European Court of Human Rights.

How long this lawsuit will last, I do not know.

The fact that I do know and that somewhat puts me at ease is that I will be living in Turkey at least until the lawsuit is finalized.

If the court decides in my favor, I will undoubtedly become very happy and it would mean that I would never have to leave my country.

From my own vantage point, 2007 will probably be even a more difficult year.

The trials will continue, new ones will commence. Who knows what kinds of additional injustices I would have to confront?

While all these occur, I will consider this one truth my only security.

Yes, I may perceive myself in the spiritual unease of a pigeon, but I do know that in this country people do not touch pigeons.

Pigeons live their lives all the way deep into the city, even amidst the human throngs.

Yes, somewhat apprehensive but just as much free.

(translated by F.M. Gocek)

ieva jusionyte, 10:42h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Friday, 19. January 2007

Turkish-Armenian writer shot dead

The Turkish-Armenian writer and journalist Hrant Dink, who was one of the writers prosecuted under Turkey's strict laws against "insulting Turkishness", has been shot dead:

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6279241.stm

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/6279241.stm

ieva jusionyte, 10:49h

... link (0 Kommentare) ... comment

Saturday, 30. December 2006

farewell to objectivity: writing about genocide

Dawn was breaking in New York when an international call stirred in bed fifty-four year old Columbia University fellow. The call was from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences announcing that the Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to Turkey’s most known contemporary writer - Orhan Pamuk. Later the same day in a telephone interview with the Associated Press O. Pamuk said that he accepted the award not just as a personal honor, but as an honor bestowed upon the Turkish literature and culture he represents. What happened on October 12, 2006, was echoed around the world in controversial headlines: “Nobel literature laureate Orhan Pamuk is voice of a divided country" (AP); “Award for Turkish writer strikes a blow for freedom” (Financial Times); “Pamuk: literary star and thorn in Turkey's side” (AFP); “Turk who defied official history wins Nobel Prize” (The Times); “Nobel prize for Turkish author who divided nation over massacres” (The Daily Telegraph); “A prize affair; Turkey and the Armenians” (The Economist).

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

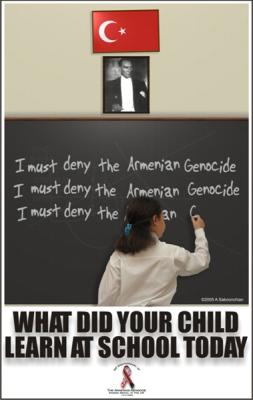

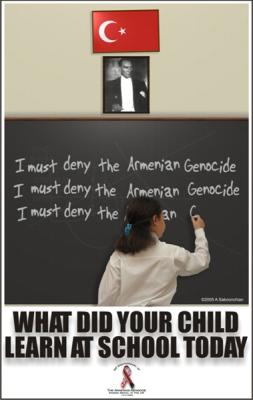

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

What is this “prize affair” that aroused so much attention from the worldwide media? Reference to the Armenians erases any doubt: the question is whether or not the massacres in Central Anatolia back in 1915 are to be called genocide. The issue was brought forward on a silver tray when at the Nobel Prize ceremony the Swedish Academy recalled the words O. Pamuk shared with a Swiss magazine back in 2005: "Thirty thousand Kurds and one million Armenians were killed in these lands, and nobody but me dares to talk about it".

Genocide in general and the Genocide with reference to the Armenian case is a difficult topic. Armenians look at 1915 as the epitome of the tragedies they suffered, while Turkey persistently rejects the charges. Although official Ankara accepts the fact that many Armenians were killed by Ottoman Empire forces in the years following 1915, it strongly denies that it was genocide. Engaged in this confrontation over history are the states of Turkey and Armenia, their nationals, Armenian minority in Turkey, Armenian and Turkish diaspora communities, as well as separate individuals, and all these actors relate themselves differently to the events of 1915. Therefore, the issue of genocide is a multidimensional one and involves politics, law, economics, history and art, to name just a few aspects of the debates which, nevertheless, begin and end with the feelings of the people. Anthropological inquiry to genocide, which is not aware of this complexity of factors, is destined to fail.

The aim of my M.A. research at Brandeis is to see how Armenian diaspora in the Greater Boston area engages in negotiations over the collective memory of the Genocide. The public space is open to contested views and due to physical and discursive encounters with Turkish immigrants the Armenians are forced to negotiate what they think are historical truths. In this new environment both groups are no longer protected under the umbrellas of their states’ propaganda. Could they re-negotiate the history and agree on the shared memory or leave plural memories legitimate? Turkish-Armenian Dialogue group attempts to bring both sides together and so enhance mutual understanding on the most personal level. On the other hand, international news from France, Turkey, Armenia, as well as the national ones - victory of the Democrats or the federal lawsuit in Massachusetts, concerning the school curriculum - set the political context for the debates about the recognition of the Genocide. Questions addressed can be numerous. How does the power of public memories work over individuals as they take on the stigmatized collective memory? In this process public institutions, that, on the one hand, legitimize identities through public memories, on the other, construct and impose them on individuals, and the trajectories of their everyday life play a significant role as they are the channels through which structural and symbolic power work on community members. Moreover, what are the limits of such collective memory in regard to an individual? Is it possible to reject the hailing? This becomes important when people with double (Armenian-Turkish) or triple (Armenian-Turkish-American) identities are taken into consideration. Finally, does the public space open the possibility of re-negotiating collective memories at all?

It is not the arguments for and against calling the massacres of Armenians a genocide that I address; therefore, in my work little reference is given to historical circumstances and the background of the conflict which are highly debated and numerous books have been written proving the position of either side. What is most important in this limited paper is to see how public negotiations over history are influenced by power relations. Power and symbolic violence in which it manifests itself are understood as multidimensional; however, their tactical and structural levels in the forms of ideology, which exists in an apparatus and its practice, and doxa are given most attention, employing Louis Althusser’s theory of interpellation and Pierre Bourdieu’s distinction between doxa and orthodoxy as a framework of analysis.

However, there is one big “but” with this research project and I feel I need to write it down. I am not doing fieldwork in a faraway place among some African tribes or with illiterate poor in the favellas of Rio. There is no time lag between being with the subjects of my research and then traveling to a university in the States to write and publish my thoughts… I am living among the people I am writing about and I do want them to read what I write, to get their feedback, their criticism. It is not easy, though, because any text is a reduction of other people’s lives and looking into the distorted mirror of an anthropologist and trying to recognize themselves might hurt them. And it is even more difficult because I have both Turkish and Armenian friends who are both interested in what I am doing.

The question for me is this - what is the right way to behave when writing about the issue of genocide? Can I remain in the realm of science? Can I remain objective? I believe that even mentioning the word “genocide” might be seen as a farewell to objective research. And going further, this question is very hard to answer. Genocide is a crime against humanity, probably the most awful one, and not recognizing it as such, fearing to give it a name, is a sign of weakness, worse, it is a sign of indifference to people who have suffered, ignorance of death. When talking to Helen, an old Armenian-American lady, whose grandmother’s arm was chopped off when she had refused to betray her son’s hiding place, feeling her pain and seeing her tears, I am simply incapable of even mentioning to her that another opinion and another interpretation of events exists. When face to face with a human being in pain arguments are powerless and insulting. But for me this is even more complex as these considerations are not produced by abstract situations or difficulties in dealing with the research subjects - my own friends are concerned. My roommate – Arto – is a Bolcetzi, an Istanbul Armenian. My good friend at Brandeis – Seyit – is a Turk. Little did nationalities matter when they found their way to my life. And they are both friends as well. Of course, never talking about politics… I would never say Seyit that maybe he doesn’t recognize the Armenian genocide because he has been subjected to ideological manipulation by the government in Ankara, who even prohibits teaching about it at school. I would never accuse anyone in this fashion. Surely, I understand the Turkish position and agree with certain statements, such as, that it was a war, that Armenians allied themselves with the enemies of the Ottoman Empire etc, etc. However, the question remains - should I situate myself in the debate over whether it was or it wasn’t genocide? Probably it depends on how I define myself… as an anthropologist? private person? journalist? public intellectual? But I feel I am all and that makes having an opinion problematic. And in either case, my opinion is too complex to call it an opinion.

When a month or so ago I posted one of these photos of the posters on my blog, Seyit sent me this link: http://www.tallarmeniantale.com/. I am not sure whether they should go side by side because they are not just two interpretations, two points of view, which neutralize one another and so produce an objective account. I think that this is avoidance of making a decision, reluctance of saying what I think. It leaves the question unanswered. But this is the easiest way to behave… Where is politically engaged anthropology now? Where is activist research in this case? What am I afraid of?

ieva jusionyte, 01:03h

... link (3 Kommentare) ... comment